Is the spiral the shape of life? From our DNA to galaxies, spirals permeate nature at every level. Spirals are found in algae, flowers, pine cones, shells, vines. Nature often moves in spirals — draining water, hurricanes, tornadoes, vine tendrils, snakes. Even our own bodies manifest spirals – fingerprints, the hair at the crown of our heads, the cochlea in our ears. So it’s no wonder we have celebrated them for millennia. The spiral signified both the wind and the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerican cultures. Architects and inventors design structures and machines based on spirals. Artists, musicians, photographers are drawn to them. Mathematicians have identified and quantified dozens of types of spirals, including the magical Fibonacci series observed in plants, shells, and even music and art.

One Circle More

Swami Vivekananda, 1899

One circle more the spiral path of life ascends

And time’s restless shuttle — running back and fro

Through maze of warp and woof

of shining threads of life — spins out a stronger piece.

Nautilus shell:

From a small point

Life flew in a curve

Of broad expanse.

The curve unwinds,

Unwinds and unwinds

In a whirling spiral

Along which man rushes,

Impelled by pain

And strengthened by hope

Of peace and brighter aims.

Josef Svatopluk Machar

from Songs of the Slav / The Spiral (1919)

The New Grange spiral marks the entrance to a Celtic tomb in Ireland older than the Egyptian pyramids. Carvings inside record lunar months and the movements of the sun and planets. The triple spiral is thought to represent Birth, Life, and Death, or Man, Woman, and Child, signifying the unending cycle of life.

The Two-Faced Whirlpool Galaxy is a typical spiral galaxy, with graceful, curving arms, pink star-forming regions, and brilliant blue strands of star clusters.

Source: NASA

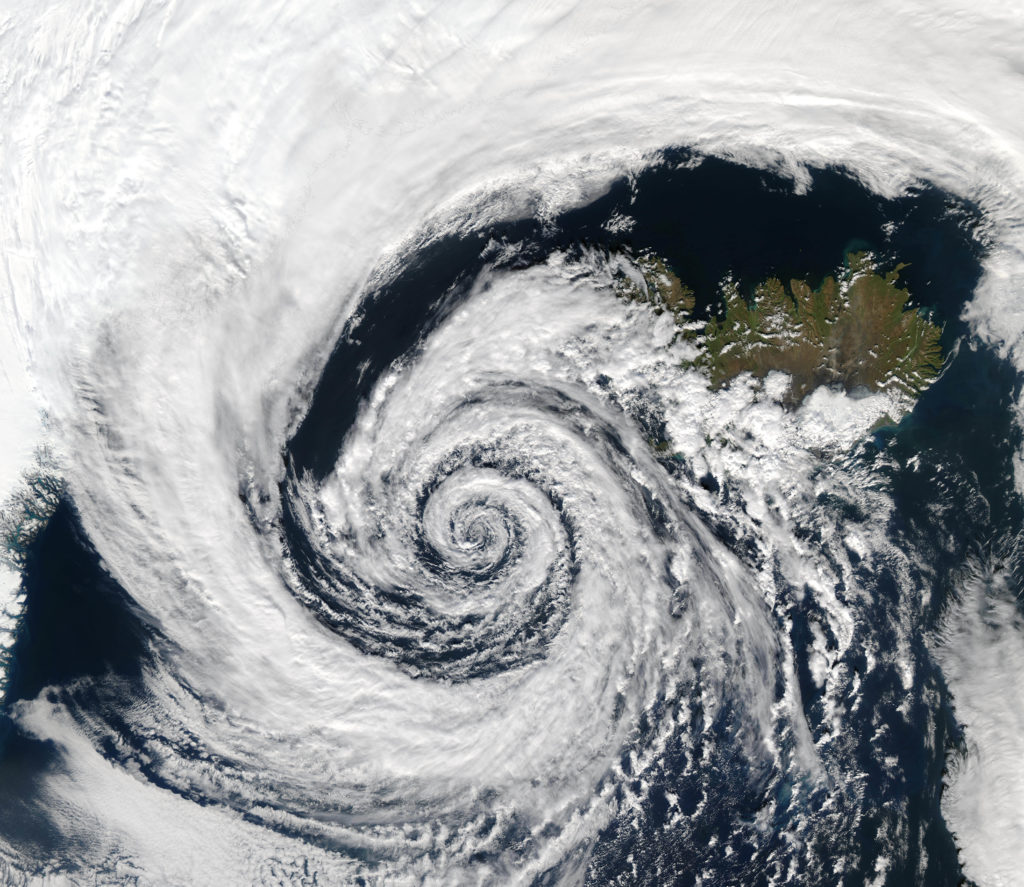

Low pressure over Iceland.

In the Northern Hemisphere,

the winds spin counter-clockwise,

a phenomenon known as the Coriolis force

(in the Southern Hemisphere, they spin clockwise).

Screwball

by Frank C. Grace

Chamaeleo calyptratus

Creating a vinyl record is both a science and an art.

The process has not changed much since the 1960s. Sound is converted to vibrations that are etched with a sapphire stylus onto a lacquer master in a spiral groove starting from the outside. Cutting is done as the music is playing and the engineer must manually create the gaps between songs by pushing the stylus toward the center. The lacquer master is then transferred three more times to negative (father) and positive (mother) masters and then finally to the stamper used to press the vinyl.

But first they have to drill the center hole in the stamper. This might sound easy, but it can be the most problematic and vexing point in the process because the hole doesn’t go in the center of the circle – it goes in the center of the SPIRAL! Just how does one find the exact center of a spiral, especially one that is made of uneven, wobbly lines? Trial and error. Yep. Even in this day and age. The slightest deviation from a perfect center hole can make the tones waver as the disc spins. The person who makes the hole watches how the arm wobbles as the needle travels through the spiral as he aligns the drill. A device reads the arm’s motion and when the wobbles even out to his satisfaction, he punches the hole. The only way to tell if the hole is correct is by pressing a test record with the stamper and playing it. If it’s wrong, they have to go back two steps and create a whole new stamper and punch a new hole. I’ve had vinyl pressing projects delayed by weeks because they couldn’t get the center hole centered. And all this has to be done for each side!

The spiral groove creates another fidelity enigma: because the record is turning at a constant speed, the closer the needle gets to the center, the smaller the circumference of the groove, which reduces the sampling rate as the sound is compressed along a shorter linear distance. A given frequency cut into the vinyl on the outer part of the record will have a longer physical wavelength than on an inner part of the record.

If you unraveled the spiral into a straight line and played it at a constant speed, the song would actually speed up near the end.

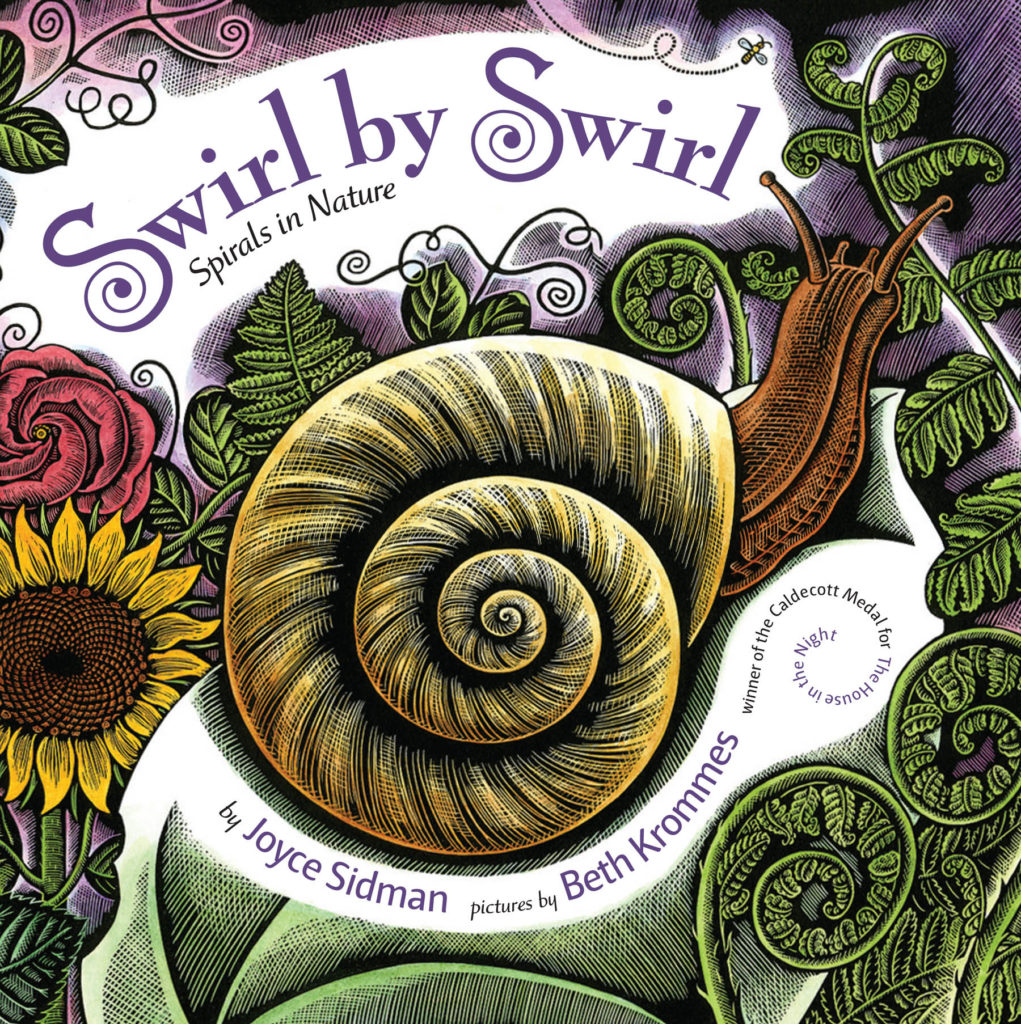

Swirl by Swirl, Spirals in Nature

by Joyce Sidman. Pictures by Beth Krommes.

What makes the tiny snail shell so beautiful? Why does that shape occur in nature over and over again—in rushing rivers, in a flower bud, even inside your ear? With simplicity and grace, Joyce Sidman’s poetry paired with Beth Krommes’s scratchboard illustrations not only reveal the many spirals in nature—from fiddleheads to elephant tusks, from crashing waves to spiraling galaxies—but also celebrate the beauty and usefulness of this fascinating shape. A Caldecott medalist and a Newbery Honor-winning poet celebrate the beauty and value of spirals.

BUY HERE: bookshop.org